The entrance to Oakview from the north reveals a beautiful valley with a breath-taking view of the Spanish Peaks and the Huerfano butte. The beauty was further enhanced by the wildlife, evidenced by the deer which were photographed in the valley in 2001. Unfortunately, the trials, tragedies, and pains of a poor life either as a wage earner in the coalmines or as weary and worn housewife, no doubt prevented them from appreciating the beauty that surrounded them.

First the coal disappeared, then the people, then the buildings. Today, it is a ghost town.

The only only evidence of Oakview's existence is the foundations of the store, post office, school, mining office and boarding house for bachelors. At one time, there were also small family homes, but their foundations barely survive. The small town began disbanding after 1932 when the Oakdale Coal Company closed the mine (Christofferson, p. 60). and it disappeared entirely after 1939.

Oakview Logistics

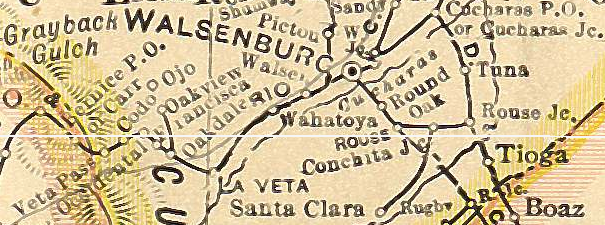

The ghost town of Oakview is located west of Walsenburg on County Road 441 between Highway 160 and County road 440. In 1920, the only access to Oakview was through the railroad which ran southwest out of Walsenburg (dark line on the map), via a short line that ran from the main line north to Oakview. The spur was built in order to carry away coal from the mine and to the market.

Oakview on the 1920 Huerfano County Map

Oakview Coordinates are NW 1/4 of SW 1/4 of Sec26 T27 R69 in Huerfano County

NOTE: All historical facts in this section are from Nancy C. Christofferson's book, Coal Was King: Hurfano County's Mining History.Oakview as a community, followed the establishment of the Oakdale coal mine in 1906 and a post office in 1907. By 1908, ten homes had been built to house the fifty men who worked in the mine. 1908 was bustling as by the year's end Oakview had forty-one houses for the workers with "two to eight rooms" each, a home for the store manager, a five-room house for the superintendent, three boardinghouses (with a total of thirty-three rooms) and additional dwellings to "house the floating population." And don't forget the saloon. A new company store was opened by the end of the year.

The mine was productive and by 1909, the Oakdale Coal Company employed 140 men full time in one capacity or another "and all the dwellings and boardinghouses were fully occuped." Oakdale No. 2 mine was opened, requiring even more workers. Evidently the local population couldn't fulfill the demands of the mine as the company brought in nine Japanese workers late in 1909, housing them in a separate boardinghouse.

The Oakview coal camp community and Oakdale Coal company continued to grow together and in 1910, the homes were provided with running water (housewives no longer having to haul water from the spring), the stable expanded to twenty-eight mules and some draft horses (needed for the record producing mines), and a new school built. But 1910 also brought about some other changes when the mine was sold to "some New York stockholders for over $300,000." It was a good bargain for the investors as the following year, the mine shipped thirty-four carloads of coal in one day, when it had been averaging thirty-five cars per week.

According to Christofferson,

The nature of the camp was now more international. In the beginning, miners were more or less "local" men. Anglos lived on one side of the camp, Spanish Americans on the other. The Japanese moved to the north end after their arrival. After 1910, more Italians and Eastern Europeans were hired.... There was also a sizeable Welsh community in camp.Night classes were held for the foreign residents to learn English, and another boardinghouse was built, bringing the total to four.

The growth of the community was evident in January 1913 when a second school teacher had to be hired for over seventy students. But the school was closed that March when three students died of scarlet fever. Modernization arrived with a moving picture show and a phone line. But 1913 also brought other changes - strikes as "Oakview was a hotbed of trouble. It was at this time [September] the four stone turrets were built to protect the camp from intruders and strikers."

In her book, Christofferson gives a great story about the strike that year, including the murder of four guards who were escorting a "scab" (who had went into Walsenburg to see a dentist because of a toothache) back into Oakview. The state militia was called in, and by the next May (1914), and the U.S. Cavalry was also called in (because of the Ludlow massacre and other strike-related battles). The strike persisted until December when it was called off.

Things were back to normal in 1915 for the mine and the community. Electricity came in November when the Oakdale Coal Company built an electric plant, and a club house in 1916.

In 1919 brought a major tragedy when a gas explosion killed 18 men out of the 150 men who were working in the mine at the time. It was said that many Japanese were also killed but their names were not released because of discrimination. Deaths in the coal mines were not uncommon.

Christofferson also tells of an interesting story about U.S. mail hold-up in 1922. By 1924 - eighteen years after it first opened - the mine closed. It was re-opened part-time in 1926, the same year that another coal company working just north of Oakview filed a million dollar suit against "Oakdale Coal company for mining the coal under the Ojo mine." No mention was made of the outcome of the suit, but the "mine did indeed undermine Ojo, and Ojo's waters filled the Oakdale's tunnels," after Oakdale closed.

The coal was gone by 1927, but a new vein was found in 1928 and the mine re-opened, but it was never the same. The company store and post office closed in 1930. By 1931 there was no mining to speak of, except for "a few miners taking out coal for local use." The mine closed permanently in 1932, the machinery sold and houses moved, mostly to La Veta. The once vibrant community of at least 800 at its peak, was "slowly dismantled by vandals who carted off doors, windows and later, everything not removed." The photograph above showing nothing but an empty field is evidence of their success. The supply company tore down the store for its materials.

"By 1933 most of the houses were gone...[and]the town reverted to a cattle pasture," which is what it remains to this day.

There were a few attempts at mining in the area up to 1939, but they, too failed. The Oakdale mine had coughed up 3.3 million tons of coal during its day and made a few men rich. But the majority of the people were the ordinary backbone of America.

NOTE: There are references below to both Oakview and Oakdale. It is unclear which is which, but from the 1920 map, the Oakdale mine may have been on the south side of the housing near the main railroad line and Oakview proper may have been the one north of the housing, just past the cemetery where there is a big slag pile and foundations. The mine offices and other buildings were just across the road on the east side.

The conditions of the coal mines were horrible, with high death rates because miners were paid by the weight of coal produced, were responsible for any safety issues to be done on their own time (which of course wasn't done), no protection from the black lung disease which could hit them later, and no pay when there was no work (no production orders for the company). Yet they had to pay rent and the company store in order to keep a roof over their head and food in their bellies.

During 1913-14 there were coal strikes by the unions. The mine owners erected gun turrents on the hills on the east and on the west sides of the valley in order to keep the miners under "control." (The turrents still exist, and the west turrent has an inscription.) The mine owners were dead serious about the miners not leaving to support the strikes in the other mines. There was a massacre (17 killed, including women and children) during this time at the Ludlow mine as the result of the clash between the unions and the owners (see Coal People).

This photo of some Oakview residents (probably taken between 1915 and 1920)

Photo supplied by Charlotte Schendel

shows a group of Mexicans and on the right, two Japanese men, according to Anna Galvan Cruz, the young lady sitting on the far right (as related by her daughter-in-law, Mabel Cruz). The identified residents of Oakview in this photo are Rebecca Suazo, aunt of Anna (standing, far left), Agustina Galvan, sister of Anna (next to Rebecca), and Jose Francisco Galvan, father of Anna (standing, with accordian)

Oakview Cemetery is located across the road from the "downtown" foundations, and just south of the slag pile from the mining operation. There are about 23 unmarked graves, but only marked evidence of four, as vandals have destroyed everything they could.

The 1920 census shows that the Oakview

Precinct 20 had 583 residents. For a summary of the census, click here.

Oakview was listed as school #32 in St Mary's District in the Huerfano County School Districts

Map cut from http://www.rootsweb.com/~usgenweb/maps/colorado/countymap/co1920/Huer20.jpg, Courtesy of Lee Zion.

Christofferson, Nancy C.. Coal Was King: Hurfano County's Mining History. 2000. The book can be purchased from Ms. Christerofferson, P.O. Box 12, LaVeta, CO 81055-0012. It covers all the coal-mining towns in Huerfano County, Colorado.

Mine Information from http://www.rootsweb.com/~cohuerfa/miners.htm

Photos not otherwise identified are by Shalane Sheley-Cruz

Clyne, Rick J. Coal People: Life in Southern

Colorado's Company Towns, 1890-1930, Colorado: University Press of

Colorado, July 2000.

![]() Return

to the Huerfano County Home Page

Return

to the Huerfano County Home Page