Copyrighted by Karen Mitchell.

From: Spanish Mission Churches of New Mexico, 1915

Used with permission.

"The very name of Taos brings up so many subjects of entrancing interest that it is likely to open the flood-gates of description, of history, of tradition, of architecture, of Indian mythology, ceremonials, and domestic customs, to such an extent that a whole volume would be filled to the exclusion of all other parts of New Mexico.

Each subject is so inviting that it is a positive delight to dwell upon it and a real sorrow to pass it by.

Who that has visited the wonderful Pueblo structures, certainly the most remarkable residential buildings in the United States, does not long to describe those unique houses of a unique people, which some have characterized as the “American Pyramids” and some as the “Human Bee-hives,” so that those less fortunate may obtain some adequate idea of their size and form and all the peculiarities of their construction?

And who that has been present at the fiestas of the people, the religious ceremonials, the dramatized folk-lore, the games of amusement or of athletic contest—all so different from the corresponding exercises of the white man—does not long to describe all these things by written word and photo-illustration, so that the new Americans of the East may have a better knowledge of these old Americans of the West? Taos is entitled to have a whole book to itself; and what a volume of varied interest it will be, when once it is worthily prepared!

In this volume, the only way to avoid the temptation to digress is to confine this chapter strictly to its legitimate subject of the churches; and that we will endeavor to do.

The first European to see the great communal houses which render Taos famous, was Francisco de Barrio-Nuevo, one of Coronado's captains. While the headquarters of the expedition were established at Tihuex, in the Rio Grande Valley near the present Bernalillo, this intrepid explorer was directed to march to the north in order to investigate and report as to the country and its inhabitants. At that time Cia was the limit of the geographical knowledge of the Spaniards. But Barrio-Nuevo quickly passed that point, reached Jemez and discovered the sulphur springs, and then crossed to the Rio Grande and proceeded up its valley, and finally came to the largest town in that section of the country, which was called Braba, and was situated on both sides of a stream, and is so well described that it is immediately identified with Taos. The Spaniards called it Valladolid from some fancied resemblance to the Spanish city of that name; but in future history we hear no mention of that attempted change, and the town of the twin pyramids is always called the pueblo of Taos.

After Coronado's time, the intermediate expeditions did not reach as far north as this remote pueblo; but when actual colonization came, under Oñate, in 1598, that energetic leader, within three days after the decision to make the permanent settlement and capital at San Gabriel, on July 12th, started to visit the northerly towns of his dominion, of which he must have heard marvelous accounts, and before July 20th had explored all the vicinity of Picuris and Taos and returned to his headquarters at the mouth of the Chama.

A few weeks later, when the Franciscan comisario, Fr. Martinez, divided New Mexico into seven districts for missionary purposes, Taos and Picuris, with all the northern country, were made into one district, and Fr. Francisco de Zamora assigned as its missionary. He commenced his work energetically, though with many drawbacks, of which an entire ignorance of the language was perhaps the greatest, and one of the first churches built in the new province was at the pueblo of Taos. In the report of Fr. Benavides, written in 1629, he states that at this pueblo there were then a church and a convento and that the number of baptized Indians was not less than 2,500; which certainly speaks well for the persistent labors of the Franciscan priest.

That this acceptance of Christianity was often only skin-deep, seems to be too evident from the fact that notwithstanding this gratifying number of baptisms, within two years thereafter the Indians of Taos killed their missionary, who was then Pedro de Miranda. The most circumstantial account that we have of this unfortunate event, is that the government furnished two soldiers, named Luis Pacheco and Juan de Estrada, as a guard for the protection of the missionary; that on the morning of December 21, 1631, they came into the kitchen of the convento to warm themselves, as it was very cold, and found the priest engaged in prayer; that they were followed by a crowd of Indians, who for some reason had become incensed against the Spaniards, and who killed the soldiers and afterwards the priest. When the Pueblo Revolution of 1680 broke forth, the missionary in charge was Fr. Antonio de Mora, who had been in service in New Mexico for nine years and who was assisted by Juan de la Pedroza, a Franciscan lay brother, who had a still longer term of service to his credit. Though Taos was the most remote pueblo towards the north, yet the arrangements for the uprising were so perfect that all the Indians were in revolt on the morning of August 10th, and both of the Franciscans soon joined the noble army of martyrs. Nearly every Spaniard living in the valley was slain, as will be stated hereafter.

Little change took place in the Mission Church through all the years of its existence. Another church was built at the Mexican town of Fernandez, only three miles away, and often one clergyman had charge of the entire religious work, both for the whites and the Indians. The Pueblo church was very massively constructed and had two towers in front. No prophet arose to foretell its strange destruction. Fernandez had become quite a commercial center, and around its plaza were the stores of traders who had become rich largely from the traffic in furs and skins. In 1846 rumors arrived of the approach over the great eastern plain of an American army under General Kearny; and later the news came that the invaders had occupied Santa Fé and taken charge of the government. The selection of Charles Bent, a resident of Taos, well known by all, as the new governor, naturally created an increased local interest, but the sentiment of the people was still opposed to the domination of the Anglo-Americans and the leaders in the revolutionary movement to destroy them had little difficulty in enlisting the aid of the Indians of the pueblo of Taos. At all events, while the leadership was in and around Santa Fé, the actual uprising centered in Taos, resulting in the killing of Governor Bent and other friends of the new government in Fernandez, and of all the American residents at the Arroyo Hondo.

Unwittingly the revolutionists were ringing the knell of the old Mission Church at the pueblo, and it is with this that we are specially concerned. The news of the revolt and the death of the governor created great excitement in Santa Fé and called for instant action on the part of the little American army and those sympathizing with it. The situation was critical. Very few troops were in Santa Fé; Kearny had marched toward California and Doniphan to Chihuahua, so that the number remaining in the Territory was very small, and they were scattered at Albuquerque, Las Vegas, and other distant points. News came that a large Mexican and Indian force was approaching from the north. Delay meant destruction, and Colonel Price, who was in command, determined to march immediately with such troops as he could muster, at the same time sending to Albuquerque for reënforcements. All the force that could be gathered amounted to 320 men, including Captain Angney's Missouri battalion and a volunteer company composed of nearly all the Americans in the city, under command of Colonel Ceran St. Vrain, who happened to be in Santa Fé at the time. In this company were Manuel Chares, Nicolas Pino, and a few other prominent New Mexicans, who stood by the new government and offered their services.

The first conflict took place at La Cañada, where General Tafoya was killed, and the Mexicans and Indians retreated to Embudo. Here they made another stand in a narrow cation, but were forced to abandon it and again to retreat, many of the Mexicans returning to their homes. This time the remainder concentrated at the pueblo of Taos, with headquarters in the mission church, within whose massive walls they fortified themselves against attack.

Meanwhile the Americans had been reënforced by Captain Burgwin's company of cavalry, which had hastened up from Albuquerque and arrived at the town of Taos in the afternoon, and immediately marched to the pueblo.

The American troops were worn out with fatigue and exposure, and in most urgent need of rest; but their intrepid commander, desiring to give his opponents no more time to strengthen their works, and full of zeal and energy, if not of prudence, determined to commence an immediate attack.

The two great buildings at this pueblo are well known from descriptions and engravings. Between these great buildings, each of which can accommodate a multitude of men, runs the clear water of the Taos Creek; and to the west of the northerly building stood the old church, with walls of adobe from three to seven and a half feet in thickness. The church was turned into a fortification, and was the point where the insurgents concentrated their strength; and against this Colonel Price directed his principal attack. The six-pounder and the howitzer were brought into position without delay, under the command of Lieutenant Dyer, and opened a fire on the thick adobe walls. But cannon balls made little impression on the massive banks of earth, in which they imbedded themselves without doing damage; and after a fire of two hours, the battery was withdrawn, and the troops allowed to return to the town of Taos for their much-needed rest.

Early the next morning, the troops advanced again to the pueblo, but found those within equally prepared.

The story of the attack and capture of this place is so interesting, both on account of the meeting here of old and new systems of warfare—of modern artillery with an aboriginal stronghold—and because the church was one of the oldest of the Spanish Missions, that it seems best to insert the official report as presented by Colonel Price. Nothing could show more plainly how superior strong earthworks are to many more ambitious structures of defense, or more forcibly display the courage and heroism of those who took part in the battle. Colonel Price writes:

“Posting the dragoons under Captain Burgwin about 260 yards from the western flank of the church I ordered the mounted men under Captains St. Vrain and Slack to a position on the opposite side of the town, whence they could discover and intercept any fugitives who might attempt to escape. The residue of the troops took ground about three hundred yards from the north wall. Here, too, Lieutenant Dyer established himself with the six-pounder and two howitzers, while Lieutenant Hassendaubel remained with Captain Burgwin, in command of two howitzers. By this arrangement a cross-fire was obtained, sweeping the front and eastern flank of the church. All these arrangements being made, the batteries opened upon the town at nine o'clock. At eleven o'clock, finding it impossible to breach the walls of the church with the six-pounder and howitzers, I determined to storm the building. At a signal, Captain Burgwin, at the head of his own company and that of Captain McMillin, charged the western flank of the church, while Captain Angney and Captain Barber charged the northern wall. As soon as the troops above mentioned had established themselves under the western wall of the church, axes were used in the attempt to breach it, and a temporary ladder having been made, the roof was fired. About this time, Captain Burgwin, at the head of a small party, left the cover afforded by the flank of the church, and penetrating into the corral in front of that building, endeavored to force the door. In this exposed situation, Captain Burgwin received a severe wound, which deprived me of his valuable services, and of which he died on the 7th instant. In the meantime, small holes had been cut in the western wall, and shells were thrown in by hand, doing good execution. The enemy, during all of this time, kept up a destructive fire upon our troops. About half-past three o'clock, the six-pounder was run up within sixty yards of the church, and after ten rounds, one of the holes which had been cut with the axes was widened into a practicable breach. The storming party now entered and took possession of the church without opposition. The interior was filled with dense smoke, but for which circumstance our storming party would have suffered great loss. A few of the enemy were seen in the gallery, where an open door admitted the air, but they retired without firing agun. . . “The number of the enemy at the battle of Pueblo de Taos was between six and seven hundred, and of those one hundred and fifty were killed, wounded not known. Our own loss was seven killed and forty-five wounded; many of the wounded have since died.”

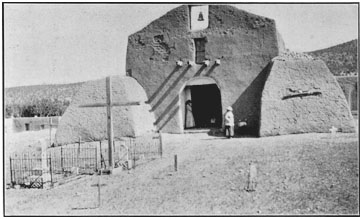

RUINS OF CHURCH, TAOS PUEBLO

Thus, not by lapse of time and gradual dissolution, but amid the fierceness of armed conflict and with hundreds of cannon balls embedded in its walls, this ancient Mission, the northerly outpost of the Christianizing efforts of the intrepid followers of St. Francis fell into ruin. Two-thirds of a century has since passed, but its walls were so massive and so strongly constructed that its remains stand almost exactly as they were left at the close of the battle, its solitary tower standing in picturesque grandeur against the clear horizon, a source of unceasing interest to the traveler and the favorite subject of every artist. The illustration shows it as it appeared in 1914.

The fertile valley of Taos naturally attracted the Spanish colonists who came to New Mexico and the officials who, from time to time, had occasion to visit the pueblo, and history informs us that at the time of the Revolution of 1680, there were about seventy Spaniards who had settled there. At the uprising they were attacked by the Indians from the pueblo and also by the Apaches who were sojourning there, and all but two were killed. These were Sergeant Sebastian de Herrera and Don Fernando de Chaves, who, leaving their dead wives and children, worked their way along the mountains to the south until they came within sight of Santa Fé, and finding that the Spaniards there were besieged on all sides, continued their journey toward the south until finally, after ten days of danger and hardship, they succeeded in joining the Spaniards who had gathered near Isleta under Lieutenant Governor Garcia.

OLD PARISH CHURCH OF TAOS

After the reconquest new settlers were attracted by the beauty and fertility of the valley, and the town of Don Fernandez grew during the eighteenth century to considerable proportions. About 1806, or perhaps somewhat earlier, the large church was erected, which until very recently was the religious center of the community, and of which we are glad to be able to present an excellent picture from a photograph. Many years ago the rear wall showed signs of weakness and quite a dangerous crack was developed, but by inserting a stone foundation and building two massive buttresses of adobe it was made secure. These buttresses formed a conspicuous feature when viewed from the rear, but do not show in the photograph here presented, which gives a direct front view.

This church was the scene of the pastoral labors of the celebrated Padre Martinez for many years. He became pastor in 1826 and continued in charge until 1856. During this long period he was not only parish priest, but he conducted the most important school which then existed in New Mexico, brought a printing press to Taos, established the first newspaper in the Southwest, and published several school-books and manuals of devotion. A full generation of the youth of northern New Mexico was educated under his personal instruction, and he thus exercised a very important influence in molding the sentiment of that section for many years. When, as a result of the inevitable clash between the old Mexican ecclesiastical methods and the new ones introduced by Bishop Lamy and the French priests, he was superseded as pastor of Taos by Rev. Damaso Taladrid, he continued to hold regular services in a chapel erected for that purpose, and fully half of the people of Taos refused to be separated from their old pastor until his death.

CHURCH AT ARROYO HONDO, TAOS COUNTY

This chapel is still standing, but has been used for other purposes since the death of Padre Martinez. It is forty-eight feet long by twenty-five feet in width and was entered by a large square door five and a half feet wide.

Some years ago a movement was started for the improvement of the old parish church and the introduction of some modern features; and this finally resulted in an effort to erect an entirely new edifice. The latter project was warmly supported by the “Revista de Taos,” and a number of public spirited citizens, and at length was crowned with success. The new structure, which was dedicated in 1914, is a very creditable building, thoroughly abreast of the times as to modern conveniences and ornamentation; but it is a subject of regret that it could not have been built on some other piece of ground, so that the venerable building which was associated with the lives of the people throughout such a long period could have been preserved as an enduring monument to the Christian zeal and devotion of the generations that are passed.

The church at Los Ranchos de Taos is one of the finest specimens still standing of the early New Mexican church architecture, and it is to be hoped that it may long be preserved in all its essential features.

THE CHURCH OF RANCHOS DE TAOS

It is massively constructed of adobe, with two towers in front, the upper portions of which are built of wood, and each surmounted by a cross. The front walls on each side of the large central arched doorway are sloped outside from the top to the bottom so as to form buttresses to strengthen the building and also add to the architectural effect. On one side of the rear, with an entrance from the chancel, is an addition about twenty feet square. The main body of the church measures 108 feet in length, inside; to which should be added the thickness of the walls. The vigas of the ceiling are all sustained by carved supports imbedded in the walls, and some of the vigas themselves are ornamented by carving.

The understanding among those best informed is that this church was built in the year 1772, and certainly, judging from appearances, it is entitled to that much of antiquity. The altar is comparatively new, in the modern French style, but the reredos behind the altar has not been modernized and apparently has remained unchanged from the time of the building of the church. It includes eight pictures of saints painted on canvas. On the north side is another reredos containing eight pictures painted on wood, and of native New Mexican workmanship. These, as well as some others on the south side, have been whitewashed over the paintings at some remote period, and the marks of that covering are not yet entirely removed. In the chancel is a large statue of Christ, which is evidently of great age. The church and the adjoining rooms are full of smaller objects of interest, less changed by the spirit of innovation than in most of the old churches, and consequently well worthy of the attention of the tourist.

No traveler who is visiting Taos and its wonderful pueblo should fail to see this church, as well as the whole town of Los Ranchos. Originally it was the home of a number of Pueblo Indians, and a few of the old houses, showing the aboriginal style of architecture, are still in existence.

The illustration presented is from a photograph giving an excellent front view of the church, together with the walled campo santo which surrounds it, and showing not only the large cross which commemorates a mission held in the parish some years ago, but a number of other crosses which mark the resting places of the departed."